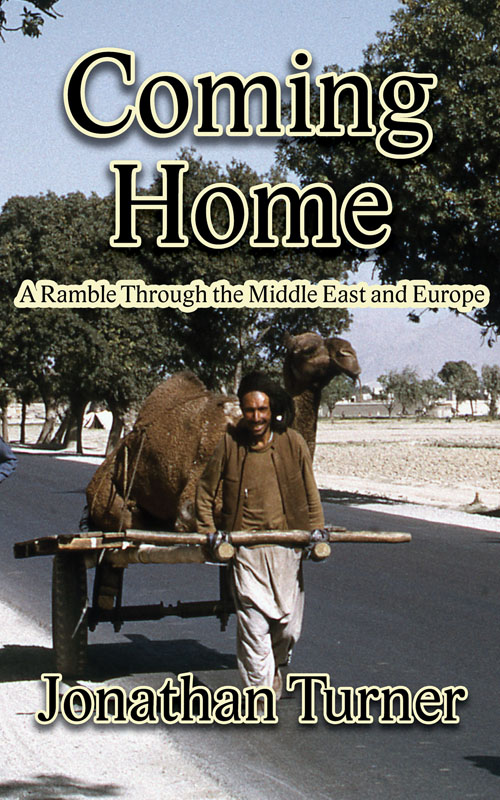

6″ X 9″, 204 pages

To purchase, click on the cover image.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Prologue

1 Pakistan

2 Afghanistan

3 Iran

4 Eastern Turkey

5 Syria – Southbound

6 Jordan – Southbound

7 Jordan – Northbound

8 Syria – Northbound

9 Turkey – Westbound

10 Greece and Yugoslavia

11 Italy and Switzerland

12 Germany and France

13 England

14 Finding Home

Prologue

Missionaries are unreasonable people. There was no earthly reason for my parents to move, four children included, from the United States to the country of Pakistan. In fact, some of their associates – church people at that – thought they were crazy. Yet, Dad felt called by Christ to go. He dreamed of preaching the Gospel to Muslims. And Mom, ever supportive, backed him up.

Dad first heard of Islam in a church history class while attending San Jose Bible College (now Jessup University). He was intrigued to learn of a group of people who seemingly believed many of the same things as Christians (such as there is one God, that God has spoken to mankind through prophets, Jesus was born of the virgin Mary, the Bible is a book inspired by God, the dead will rise to face judgment, etc.), yet who did not accept Jesus as the Savior of the world.

Dad broke into his professor’s monologue. “Since these people are so close to us, why aren’t we helping them cross the threshold [of faith]?” he asked in starry-eyed innocence. The professor, annoyed at being interrupted, answered Dad’s inquiry with a grunt and went on with his lesson plan – thus earning Dad’s life-long disdain. Over the years we kids heard Dad grump, more than once, about how his professors failed to prepare the students of his generation to face the challenges and opportunities of the post-World War II years. “They had no vision. They had no idea what was going on in the world, much less how it would affect the church!”

In addition to the professor’s indifference, starting a family and helping found new churches pushed the the idea of preaching to Muslims to the back of Dad’s mind. Not long after graduating and being ordained as an evangelist in 1947, Dad moved the family to Vancouver, Washington where he and Mom had been invited to organize a church. To support the family while doing so, Dad worked a variety of jobs from digging ditch to carpentry. As of this writing the Minnehaha Church of Christ, which Dad and Mom founded, still meets in the same building Dad helped construct.

During his time in Vancouver, Dad also cooperated in establishing a college, Northwest School of Evangelists, whose purpose, as its name implies, was to train evangelists. The school survives to this day as the Northwest College of the Bible.

About the same time, Dad’s interest in Islam burst into flame again. The catalyst was an article in the November, 1954 Reader’s Digest written by James A. Michener titled, Pakistan: Divided It Stands. On the basis of the article Dad figured that the best odds of going to any Muslim country lay with Pakistan as, at the time, Pakistan was a close ally of the U.S.. He laid the proposition before Mom and asked whether she would be willing to go. “If that’s what you think the Lord is calling you to do, I’m willing.”

But it’s one thing to fantasize about proclaiming Christ in another country, actually doing it is not so easy. Dad had neither the money nor the training. Further, he faced active opposition from other church leaders who resented his decision. They thought he ought to concentrate his energies on teaching in the school and evangelizing the local area. Also, the family was growing. In 1955 I put in appearance – the fourth of an eventual five children. But unreasonable people don’t let trivialities like that stop them.

In 1956 the only institution of higher learning that had any kind of program relevant to the part of the world where Dad wanted to go, was the University of Pennsylvania. Dad borrowed enough money to fix up the small house we were living in so it could be sold. Then he used the money from the sale to move us to Philadelphia. By the time he paid the first semester’s tuition, he had only enough left for a couple of month’s rent. To support the family while he studied, he again worked a variety of jobs including transcribing medical records, hanging garage doors and carpentry. While describing his struggles in later years, his resentment of having to compete with people who had full-ride scholarships from the U.S. Department of State was still palpable. As if having to earn a living as well as carrying a full academic load were not enough, he and Mom also started another church. Did I say that missionaries are unreasonable people?

But Dad was not yet a missionary. After earning his Masters Degree in South Asia Studies, it didn’t look like he was any closer to going to Pakistan than before moving to Philadelphia. He still had no support nor any means to go. To complicate matters, Mom and Dad were very happy in the church they started. One day Dad had a one-person prayer meeting, “Lord you know the reason we came here. I felt that you wanted me to prepare myself for service in Pakistan. Was I mistaken? We’re happy here. If you want us to stay, we’re willing. Please just give us direction.”

After that, miracles began to happen. Dad received a phone call from an old friend, Doctor Bigelow. “Hey, Lee. Whatever became of your idea of going to Pakistan? Is it still in the works?”

“Well, Wayne, there are two problems. One, I don’t have any money. Two, the last time I checked, Pakistan wasn’t issuing any visas.”

“Why don’t you take another crack at getting the visa and let me see what I can do about some money?”

On the strength of that conversation, Dad went to the Pakistan Embassy in New York and applied for a visa. He’d already received admission to study at the University of the Punjab in Lahore, Pakistan. The American secretary at the embassy was not encouraging. “Mr. Turner, do you intend to preach while you are in Pakistan?”

“Why, yes – if they ask me to.”

“The last person to apply was a lady who was just going to be a dorm mother at a school. They turned her down. I don’t think you’ll fare any better, especially if you’re going to preach. However, I’m not the one who makes the decision. I’ll take your application to the officer upstairs.”

About a half hour later she came back. “Mr. Turner, your visa will arrive by registered mail, on Monday.”

Next came the problem of transportation. Flying was far out of reach, so Dad made the tours of the steamship companies. Passenger liners were as unrealistic as flying, which left the tramp freighters. Nobody had any berths available. In some cases, they were booked months, if not years, in advance. However, after telling Dad there was no room, one agent asked him to call back in a couple of days. As I recall the story, when Dad talked to the man again, he was told the same thing. Finally, after having Dad call him back several times the man said, “Mr. Turner, a very strange thing has happened. These ships have a total of twelve berths. They have been booked for months. However, six people have disappeared into thin air. I have been unable to contact them. If you still want the berths, they’re yours.” That is how, six weeks after my father’s prayer meeting, our family came to occupy half of the passenger list on the US Steel Age, a surplussed Liberty Ship from World War II. A month later, in September of 1960, the ship decanted us onto the quay in Karachi, Pakistan. I was not quite five years old.

What happened during the next fifteen years is the proper subject of different book than this one. Suffice it to say that Dad threw himself into language study, preaching, teaching and establishing churches. With the addition of my youngest sister who was born in 1963, Mom devoted herself to raising us five kids, helping in a medical clinic, teaching hygiene and child-care classes and tutoring Pakistani young people in English.

Except for two breaks, our home was in the city of Lahore the entire time. We took a long furlough back to the States in 1965-1966. Then, we lived for six months in Kabul, Afghanistan while waiting out the Pakistan-Bangladesh War.

A major change in emphasis came in 1969 when Far East Broadcasting Associates asked Dad to start preparing radio programs for them. We built a recording studio and in 1971 began airing the first gospel programs ever recorded in the Urdu language. By then, all of my siblings except my youngest sister had returned to the States to complete their education, start families of their own or pursue careers.

It was in the studio that I came into my own. The technical work fascinated me and I happened to have an intuitive knack for mixing and recording music. I didn’t realize until much later what a privilege it was to have the opportunity to work with some of the top recording artists in Pakistan.

I graduated from the Lahore American Society (L.A.S.) high school in 1973 but decided to stay on the mission field for another two years. There were several factors in the decision. Like all American young men of that era, I had to register for the Selective Service when I turned eighteen. However, Congress ended the military draft the same year I graduated. Suddenly, there was no need to obtain a college deferment to keep me out of the Vietnam War.

A second reason to stay in Pakistan was I was heartily sick of school and wanted to take a break. I was spiritually drained from trying to maintain my moral standards in an environment which often had little sympathy or tolerance for those standards. (Much to my dismay, the kids of other missionaries were sometimes the worst offenders. I suppose they thought they were proving something to the rest of us by openly repudiating the beliefs and morals of their parents when their parents weren’t around.) However, I had no idea what I would do with myself in the States if I didn’t attend school.

Another reason to stay in Pakistan was my father. Dad was a complex man and my relationship with him was also complex. He was driven, strong willed, opinionated and tended to give short shrift to those whom he deemed were unnecessarily stupid or not living up to their potential. In addition, he was often at a loss to know how to show love and affection. At times he could seem oblivious to the emotional needs and concerns of his family. Nor was he particularly consistent. In contrast, he could be amazingly sensitive and compassionate to outsiders. He could sympathize with others and was a soft touch. He was one of those charismatic individuals who causes the center of gravity to shift when they enter a room. His ability to connect with other people always amazed me. I have seen him meet total strangers and within minutes be engaged in deep spiritual conversation. I’ve witnessed him develop rapport with both street beggars and princesses.

Growing up in the shadow of such a strong personality was not easy. Like many people who grow up in the shadow of someone who is “bigger than life,” it took me longer than it should to grow up and mature. There’s no question I was a “late-bloomer.” I was also introverted and shy. Meeting new people was difficult. (It still isn’t easy!) After our return to the States I would literally break out in a sweat before making a phone call – particularly a business call or to someone I didn’t know. This aspect of my personality was something Dad could never fathom, let alone sympathize with. I have my own share of stubbornness, opinions and temper. Mix in a good portion of teen know-it-all, and you have the potential for plenty of conflict. In time we learned to accommodate one another and established a good working relationship. But at the time I decided to stay in Pakistan, that lay several years in the future.

If my relationship with my father was so rocky, why did I stay? Because along with the turmoil and misunderstanding; in spite of all the times I was infuriated with Dad, I also loved him. Dad had always hoped that at least one of his children would follow in his footsteps. As time passed it didn’t look like that would happen. As my older siblings chose other paths his hopes came to rest upon me. I knew that if I left it would be a crushing disappointment to him. So, I stayed.

There was another factor, too. As an incentive for me to stay an additional two years, Dad held out the possibility of making a tour of the Middle East when the time came to move back to the States. He had wanted to make such a trip for many years. When we came back to the States on furlough in 1965, he planned to ride through the Middle East with my brother on motorcycles. It was probably a blessing that he didn’t have the money to do it as, during that era, some locales had the disturbing habit of stoning motorcyclists. But now, he began to dream again. We would drive our 1955 vintage Willys Jeep station-wagon through Bible lands, camping out along the way. For a young man with a touch of wander-lust in his blood the prospect was alluring.

Did I happen to mention that missionaries are unreasonable? There was nothing reasonable about the trip Dad proposed. Much of it would be on rugged, unpaved roads where services and spare parts were unavailable. If we had mechanical trouble we would, for the most part, have to deal with it ourselves. Should we have an accident or become ill, medical facilities were few and far between. We would have no way to communicate with family or friends except by letter – and, in many places, mail service was iffy. Since we would have no fixed address and could not predict with any certainty where we would be at any given time, the only way for someone to contact us would be to write a letter in care of the American Embassy in those places where they existed or to “Postes Restant” (General Delivery) at the main post office of major cities, and hope that we would happen along sometime or other to pick up our mail. We would be driving through parts of the world where the population, if not actually hostile to Americans, had no great love for them. People, by the way, whose language we could not understand or speak.

These undoubted facts were not the only thing which made the trip unreasonable. There was yet another catch. Automotive engineers know more now than they did then and the Pakistani roads were murder on vehicles. We used to service the Jeep every 1,000 miles – and it needed it. Before we could even contemplate making the trip we envisioned, the Jeep would have to be rebuilt from the ground up.

On the other hand, though we didn’t realize it at the time, the window of opportunity to make such a trip was rapidly coming to an end. The door would close in only another three and a half years. The demonstrations and riots which led up to the overthrow of the Shah of Iran began in 1978. After the Khomeini regime took over the country in 1979 it became impossible for Americans to travel there. Not to be outdone, the Russians invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Between the Russians, the Mujahudin and the Taliban, an American courted death by setting foot in Afghanistan. Americans are not free to wander where they will even in Pakistan anymore. To travel through the tribal areas to reach the Pakistan-Afghan border as we did, now requires a special permit. Even should a permit be granted, it is infinitely more dangerous to travel there than when we did because the area is controlled by fanatical Muslim groups who view Americans as infidel enemies. So, in retrospect, we made the trip at the right time, unreasonable though it was.

Most of the work of rebuilding the Jeep fell to me. I went over the frame inch by inch and welded any cracks I found. Then, I redid the springs and beefed them up with extra leaves. I replaced the badly worn intermediate shaft in the transmission which was making a lot of noise. Instead of trying to refurbish the worn-out engine, I found a replacement in the junkyard with no discernible wear on it and rebuilt it. I changed out wheel bearings, universal joints and tie-rod ends. Since there were no line-up shops in Lahore I made my own tools to align the wheels and suspension.

Installing a new rear-wheel bearing in preparation for our grand adventure.

While I was redoing the chassis and engine, Dad hired some men to dent out and repaint the body. While they were at it, he had them fashion a false floor under the station-wagon bed out of twenty-gauge sheet steel. He filled the gap between the floors with fiberglass insulation. We intended to make the trip in summer and I presume the idea was to keep the interior of the Jeep a little cooler by preventing the heat from the exhaust system from coming up through the floorboards. I’m not sure the perceived benefit was worth the extra weight.

While re-wiring the entire vehicle I rigged up a twelve-volt battery and alternator in addition to the original six-volt generator and battery. This involved building a regulator from scratch as I couldn’t find one to buy. We used the twelve-volt system to power a mini fridge and washing machine we installed on tracks that pulled out over the tailgate. Along one side of the body we built a clothes closet. We also built a formidable roof-rack. In it we installed two large auxiliary gas tanks and mounts for two spare tires. Since we intended to make the trip during the summer we planned to sleep on top of the rack in cots. A canvas top covered it all. I also installed a few extras like additional gauges on the dashboard, an air horn to supplement the original equipment and extra lights.

All the comforts of home. Washing machine, fridge and water filter. A gas stove is on a shelf above the water filter.

Only one thing worried me. After I tuned the engine I could hear a slight anomaly. I didn’t know what it was but something was not quite right. However, Dad couldn’t hear it and brushed my concerns away. In hindsight, I suspect that the project had already taken longer than he anticipated and he couldn’t justify any more expense. It was easier to pooh-pooh a hypothetical problem he couldn’t hear than to authorize more messing about.

The decision to leave Pakistan was not straightforward either. Aside from not feeling that he could justify asking me to remain in Pakistan for more than two years after I graduated high school, there was another aspect to the decision. It was becoming increasingly difficult to obtain long-term visas to stay. For example, it took numerous visits to the capital, Islamabad, plus influence from high-placed friends just to receive permission to return from a short trip to the States to attend my sister, Lois’, wedding. My parents concluded that it wasn’t worth the effort to extend our stay after our current visas ran out.

Not only that, we were living, so to speak, under a cloud. Our integrity had been questioned and Dad was very uncertain about the future. He wondered if he could still be effective if he remained in country. The situation was this: My father tried to train some men as leaders for the churches he started. Unfortunately, two of them decided to profit from Dad’s compassion. They cooked up a scheme where they persuaded people from outlying villages to bring Dad various tales of woe and need. Since Dad often didn’t have the time to investigate, and was trying to shift the burden to local leaders anyway, he would send these guys out to look into the situation. Naturally, they would come back saying the need was genuine, then would split anything Dad coughed up between themselves and the petitioners.

It wasn’t long before we started to hear rumors that something was amiss. We had our suspicions but couldn’t prove anything. Without Dad’s knowledge or consent I eventually got the goods by bugging a conversation. When Dad found out what I had done he was livid. “You have broken trust. You’ll never be able to build a strong church if everybody is suspicious of everybody else. You can’t have everybody wondering if they are being spied on and if their words will be used against them.” And so, I learned the hard way that ends do not justify means. Fortunately, the evidence I collected wasn’t needed because one of the fake charity cases couldn’t live with his conscience and confessed to my father what he had done. This led to church discipline for the two who ran the swindle.

It did not end well. Instead of repenting, the men sent a scathing letter against my father back to our sponsoring congregation. The church was so concerned over the allegations they sent a team to Pakistan to investigate.

During the investigation the men whom we had caught stealing also accused me of manufacturing evidence by clever editing of the tapes in my possession. Since this was not long after the Watergate scandal which brought down President Nixon, there was a surface plausibility to the accusation.

The investigating committee cleared Dad and me of all charges but the whole incident left a bitter taste in Dad’s mouth. He resented that the committee came to Pakistan without informing him beforehand and had a hard time accepting that the committee’s major concern was to protect his reputation from false accusations rather than lend substance to the accusations.

Not long afterward, a trusted friend in the police department tipped Dad off that someone, presumably one of the men in the charity scheme, had denounced him as a spy. The informant alleged that we were using the recording studio for espionage. I’m not sure how seriously the Pakistani government took the accusation but I do know that our house was under surveillance for quite a while and our telephone was tapped. All this may have merely been an expression of the usual Pakistani paranoia without having anything to do with the accusation. In any case, we took no chances. As soon as Dad received the tip we dismantled the studio and moved the equipment to another location. When it became practical to do so, we sold the gear to other mission groups.

Closing the studio was another incentive to leave Pakistan as we were no longer able to carry on what had become one of the major focuses of our mission work.

As already stated, we intended to make the trip during summer. We envisioned sleeping under the stars in cots up in that roof-rack. This would have the added advantage of saving on hotel bills. Alas, it was not to be.

My mother and youngest sister flew back to the States in July, 1975, leaving Dad and me to finish closing things down. It took much longer than anticipated. Among other things, Dad needed time to finish the publication of a book he had translated into Urdu. The problem was that our visas were running out. When it became clear that we wouldn’t make our deadline, Dad explained the situation to the police and received an extension. After going through this routine several times, the police regretfully informed him that they had run out of latitude. This was the last extension they could grant. When it ran out we would have to leave whether we were ready or not.

We had shipped many of our things as sea cargo. However, there was still a lot which we had to take overland with us. The Jeep was rated as a half-ton truck. We ended up packing a full ton into it – mostly tools and books. In addition, we pulled another thousand pounds in a trailer.

We also intended to take our little mongrel dog, Mutt, along with us. However, we found out that England imposed a six-months quarantine period for all animals. This made it impractical to take him after all. Somehow the little beggar figured it out as soon as we made the decision. Before, he showed the greatest interest and excitement in all the packing and preparations. Right after we decided we had to leave him behind, the light went out of his eyes and he retreated under a bush in the yard. He lost all interest in the proceedings. How he came to know is a mystery we have never understood.

Finally, the fateful day arrived. The packing was done. We said our final goodbyes. For good or ill, we took off on our great adventure.