Home » Blog Posts (Page 6)

Category Archives: Blog Posts

In The Beginning

An alternate metaphor for creation.

No matter where you stand in the Creation/Evolution debate, I suspect that this entry will peeve the socks off of you. Here’s why: I am of the opinion that most of the debate; most of the arguments for and against; most of the evidence which is bandied about by both sides, is totally irrelevant. That statement, alone, is justification enough for people in both camps to want to crucify me. But there is method in my madness. Until you’ve had a chance to figure out what it is, please put your hammer and nails away.

Now, right off the bat, a bunch of people will jump to the conclusion that I think it is irrelevant whether we were created or merely evolved. I didn’t say that. Whether God exists and, if so, whether He created the universe and everything in it – including us – is a question of extreme importance. It’s not the question, but what is said about it, which I think is largely irrelevant.

A personal odyssey

While I was growing up, just about the only things I ever heard about evolution were derogatory statements about how stupid it was and how only fools would believe in such nonsense. I don’t remember ever being taught what evolution is or having a serious discussion about what might be wrong with it. It was just ridiculed. Therefore, it was quite a shock to learn in High School biology that evolution has a logic of its own. It is something which can be believed by intelligent people. It really does make sense – provided, of course, that you are willing to accept certain premises. At the time I was too uninformed to grasp the implications of some of those premises. Nor was I experienced enough to spot some of the logical fallacies and the faulty science which was presented. In later years, when I was sharp enough to spot such things, I discovered that evolutionists don’t have a corner on logical fallacy and bad science. Many creationists have the same problem.

I will say, though, that my High School teacher went out of his way to provide a balanced view of the whole subject. Partially as a result of my respect for the teacher and his even-handed approach, I went through a stretch of several years where I believed that God created the universe and got life started, but that He used the mechanism of evolution, particularly natural selection, to develop more complex forms of life.

Sometime during my early 20s the preacher at the congregation I was attending taught a series of lessons on evolution. Much to my surprise, he didn’t go into a bunch of scientific arguments to prove evolution wrong. Instead, he approached the whole subject from a philosophic and spiritual angle. He pointed out what the philosophical underpinnings of evolutionary belief are, and what the end results of those philosophies are. Frankly, I don’t remember very many specifics of what he said. But that series of talks helped me realize that I could not ride the fence. There is a clear-cut choice to be made between two opposed and irreconcilable belief systems. The creation accounts in Genesis are actually representative of a particular philosophic outlook. Likewise, evolution theory is an outgrowth of another philosophic outlook. These philosophies or belief structures are mutually exclusive. They cannot both be true. You’ve got to pick one or the other. Though I still had doubts, I came down on the side of creation.

Several years later, as an intellectual exercise, I tried to set all my beliefs and prejudices aside, (as though that were possible) and take an unbiased look at the question of origins. In some ways I was reluctant to do so for fear of what I might find. As it happened, the results of this quest were very beneficial and greatly reinforced the decision I had made earlier in favor of creation.

My reasons for belief

There were several things which helped persuade me that we, and the entire universe, came into being through an act of divine creation. One was symbiotic relationships. The odds of one complex organism developing into its current form are staggering enough. The odds of two completely different, yet interdependent organisms doing so simultaneously is orders of magnitude more improbable. That there are not just one, but dozens, of these relationships in nature stretches incredulity to the breaking point. The most common symbiotic relationship, and one for which I can see no evolutionary benefit, let alone necessity, is the one between male and female. Both systems must not only work perfectly, but synchronize with the other, or the species dies.

Yet, improbable things do happen. I’m told there is mathematical proof that the highly improbable often does occur. Since anything much beyond basic math goes completely over my head, there is no way for me to check the proof. I’ll just have to accept it as accurate until somebody else demonstrates otherwise. Lest somebody trot out the lottery as an example of this occurring in every-day life, let me point out the fallacy in the illustration. It is true that regardless of the odds of any one person winning the lottery, somebody does win it. But to equate the probability of winning the lottery with the probability of something evolving is a false analogy. Assuming the integrity of the lottery commission, it is fore-ordained that someone will win. There is absolutely nothing which says that evolution will occur at all – unless you are willing to concede that evolution is predetermined. And, if something or Someone is there to predetermine it, there is no need for evolution at all. If something or Someone is capable and powerful enough to predetermine evolution, then there is no logical basis for excluding the possibility that that same something or Somebody created things as they are.

Reason 2

A lot of people like to ridicule the church of the Middle Ages, often unjustly, for holding back science. Yet there is one medieval belief which evolutionists doggedly hold on to even though it flies in the face of all observation and experimental evidence. It’s the belief in spontaneous generation. In order for something to evolve at all, the threshold between the non-living and living must first be crossed. That has always seemed an impossible hurdle to me. It’s interesting that in all the brouhaha about the experiments where some amino acids were formed by shooting electrical sparks into gas mixtures, most commentators failed to mention a few things. They neglected to point out that the experiments were made under very controlled conditions. Conditions which were very, very different than anything which ever existed on early Earth. They also neglected to mention that a few acids weren’t the only things produced by the experiments. They also produced deadly toxins which would kill all life. I won’t go so far as to accuse anyone of deliberate dishonesty, but it does smell of self-delusion.

Reason 3

For many years, I’ve suspected that life, instead of evolving, may actually be devolving. In other words, each succeeding generation is, on average, somewhat less capable and viable than the preceding one. Recently I came across something which not only bears this out, but strengthens my belief in creation. To illustrate, I’ve spent a good portion of my life dealing with audio. I’ve spent more hours than I care to think about behind a mixing console, editing and designing and operating sound systems. Along the way I’ve learned that editing and the tailoring of sound is a subtractive process. It mostly involves the destruction of information.

Yes, it is possible to manipulate sound, but only if it first exists. If it isn’t there to begin with, you can’t manipulate it. Similarly, once material is removed, there is no way to re-create it, even in theory, from what is left. There are many illustrations of this. I’ll give you but one example. That MP3 you’re listening to on your Ipod contains much less material than in the original. In order to fit it into a small file size, the audio is compressed. This is done by throwing away the (hopefully!) least important information. The process cannot be reversed. The information is gone and there is no way, even in theory, to predict what should have been there. This is why MP3s can never be restored to the full quality of the original. It’s also why its inadvisable to edit an MP3 and then store it again in the same format. Each time you do, you lose even more quality, which cannot be restored.

The same sort of thing happens in genetics. There are many ways to lose genetic information. In all the experiments which have been performed, no mechanism has ever been found that increases the amount genetic information. Where did the extra information, let’s say a horse has in comparison to a fly, come from? As far as I know, there isn’t even a natural process to repair or replace the defective information caused by mutations, let alone something which would generate the extra information required for more complex organisms to evolve from less complex ones. Clearly, something else is at work. I think it points to creation.

Reason 4

The thing which convinced me the most, however, is the fact that we human beings have a sense of right and wrong. I don’t see how moral sensibility, convictions, spiritual awareness and the concepts of ‘ought’ and ‘should’ could ever be produced through a process of evolution. It simply doesn’t make sense.

God’s dilemma

Now I’m sure that there are plenty of people who are more than willing to poke holes into every reason I’ve given for my belief in creation. They’ll point out that the data I’ve mentioned is, at best, ambiguous. I agree with you that there is no definitive and indisputable proof for creation, or even the existence of God. In fact, that is precisely one of the points I’m trying to make.

So then, if God really exists, why does He make us jump through all these intellectual hoops? Why doesn’t He show Himself to us openly? Why does He leave room for doubt? On occasion I myself, have wished that God would disclose Himself more openly. But think about it from His perspective for a minute. How can God disclose Himself to us without also destroying our choice of whether to believe or not? If the Bible is correct in saying that God desires our love, how can God receive it if He takes away the choice to reject Him? God wants our love freely given, not grudging acknowledgment of His existence.

Because God, if He exists, cannot manifest Himself to us without destroying our freedom to disbelieve, there will always be a certain amount of ambiguity in the data. How you interpret the data depends largely on the philosophical outlook you bring to it. For those whose philosophic outlook embraces the concept of God, the evidence for creation is overwhelming. For those whose philosophic construct excludes God, there is no alternative to evolution. Therefore the data must be interpreted to support that theory.

Digging myself in deeper

Along the way, I’ve noticed plenty of absurdities on both sides of the aisle. For example, I think there’s a fundamental contradiction at the heart of much of the environmental movement. Many of those in the movement are fervent evolutionists. That being the case, I have never understood why they get so upset at the loss of a species or three. If natural selection and the “survival of the fittest” really are the agents of evolution, it seems to me that if a species is eliminated, it only proves it wasn’t fit to survive anyway. The fact that people get upset about it says to me that something besides evolution is at work. They are protesting on the basis of moral conviction which, itself, cannot be a product of evolutionary processes.

Evolutionists also like to accuse creationists of taking a “God-of-the-gaps” position. In other words, the only reason we need God is because we can’t yet explain something. Given enough time (and research dollars!) however, all the mysteries of nature will eventually be explained. Once we understand the mechanisms involved, there will no longer be room for belief that God, if He exists at all, created anything. There are at least two fallacies with this argument. One is that it conveniently ignores the problem of how energy or matter came into being in the first place. Regardless of the mechanism by which everything has since been ordered and arranged, how did it come into being to begin with? Evolutionists have no convincing answer.

A second fallacy is to assume that because something could occur in a certain way, that it actually did, or does, occur that way. For example, it’s possible that I could enter these words by dictating them into speech recognition software. But just because it’s possible does not prove that’s how I’m doing it. Similarly, just because there may be a purely naturalistic means of obtaining a certain outcome does not, in itself, prove that the outcome was obtained by purely naturalistic means. Nor does the existence of a naturalistic process exclude the possibility that God exists or that He is involved in that process. On the contrary, if God invented nature, we ought to expect that much of what He does is through naturalistic means.

Creationists are not immune from absurdities either. For example, one of the arguments I’ve heard in support of the young-earth hypothesis is that the oceans aren’t salty enough. The argument goes that the oceans would contain much more salt than they do if the earth was older than several thousand years. While making this argument the creationists fall into the same trap as they accuse the evolutionists of living in – uniformitarianism. But how can you possibly know how salty the oceans ought to be based on current erosion rates, or the current size of the oceans, or the current rate of precipitation, or the current salt content of the earth, etc., etc.? You’re assuming that the rate of change has stayed relatively constant. But how can you know that? You can’t.

My biggest beef with those in the creationist camp, however, is that you are fighting the wrong battle. The creation/evolution debate is not primarily a scientific one. As I stated before, it’s really about philosophy, not science. The data will always be somewhat ambiguous. There will always be another scientific factoid which throws doubt on the proof you have just so confidently asserted. You will never be able to prove creation and, therefore, the existence of God as a scientific fact. If such a god could be proven he wouldn’t be worth believing in, anyway. If God exists He, by definition, must be beyond nature and, therefore, outside the space-time continuum we experience. He transcends nature and, therefore, transcends science. You will never see Him unless you look through the eyes of faith. If we have faith, then I agree, the universe is filled with evidence which points to God. But without at least an inclination toward faith, there will always be a way to explain the evidence away – until, that is, God breaks through His self-imposed curtain and every eye beholds Him. Only then will there be no need for faith. Please don’t misunderstand me. I agree that there is value in pointing out scientific error and teaching correct science. There’s no doubt that many are helped to find Christ by your clearing away some of the misconceptions that are out there. But never forget that science, even good science, is not the answer. It’s a spiritual battle, not a scientific one. As a friend of mine pointed out, it’s not really so much about evidence as it is about morals. When you get right down to it, most people don’t refuse to believe because of the lack of evidence, but because they don’t want to submit to God’s authority. They want to do their own thing.

I haven’t actually done this, but let me pose a couple of theoretical questions which illustrate just how slippery ‘proof’ can be. For the sake of discussion, if I were to ask those in the evolution camp to describe how the universe would appear if creation were true, I expect they would answer, “Just about the way it does now.” Similarly, if I were to ask those in the creation camp to describe how the universe would appear if evolution were true, I would expect them to answer, “Just about the way it does now.” Same end state, same data, two vastly different different interpretations. How you get there depends on your philosophy, not science.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Now that I’ve managed to thoroughly alienate everyone in both camps, do I have an alternative to suggest? Well, ahem, yes I do. Hang on to those hammers and nails a little bit longer.

While giving a talk on Genesis, several years ago, a speaker posed an interesting question. He asked something to the effect of, “If a couple of days after God created him, Adam took his chain saw and cut down a tree, how many rings would it have had?” The point of that fanciful question was that if the Genesis record is correct, then most of the plants and animals must have been created in a mature or adult state. That concept got me to thinking. If, at the time of creation, the plants and animals appeared older than they actually were, is it possible that the same applies to nature and the universe as a whole? If, as many think, the six creative days of Genesis refer to actual days rather than eras, it must be so.

But if the universe and the Earth, in particular, are as young as Genesis seems to indicate, why would God make them appear older than they are? When I ran the idea that the universe might look older than it is by a believing friend of mine, he rejected the notion out of hand. His reason for doing so is that God is honest. To make the universe appear a different age than it is, would be deceitful. I replied that God hasn’t deceived anyone. In His Word He’s told mankind precisely what He’s done. My friend wouldn’t buy it, even though he believes the Genesis account.

It wasn’t until just recently that my thoughts came together in some sort of coherent way. I think I now have a decent construct to explain what’s going on. First, I’ll try to describe my theory in quasi-scientific terms, then by using a metaphor.

A graph for all seasons

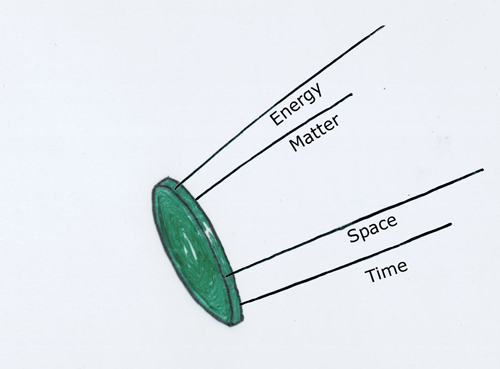

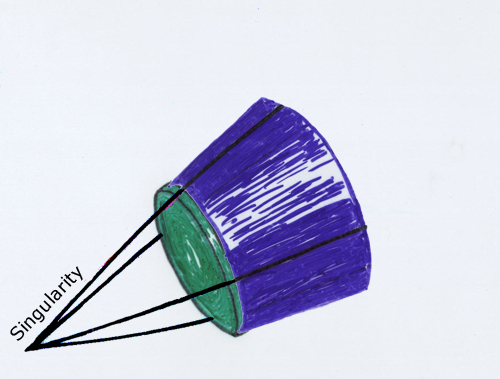

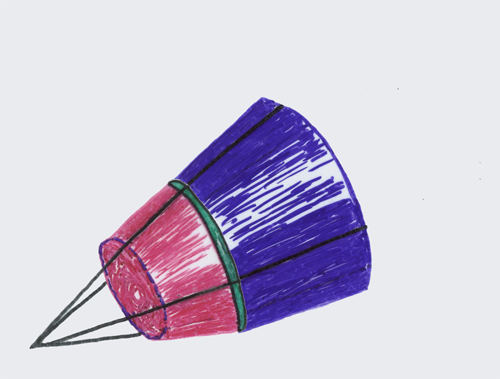

Since it’s a little hard to explain my concept just in words, I’ve drawn some diagrams to help you visualize what I’m talking about.

Consider a disk. This disk represents a slice of our experience at the present time. By ‘our experience’ I mean not only our individual existence, but also the state of the whole world, our universe and the whole of nature. It should be obvious that the physical laws which govern this slice of existence are uniform and consistent. If chemistry, physics, thermodynamics and the like were erratic, or were self-contradictory, the universe, and we along with it, could not exist.

Now think of the disk as being bound, or defined, by several constraints. One of them is time, another space, another matter, a fourth energy and so on. I don’t claim that these are the only constraints – there may well be other dimensions – but these are enough to illustrate the concept. For the purists among you, yes, I am aware that these dimensions, for example matter and energy, can be converted from one to another. Think of the rim of the disk as a visual representation the transforms.

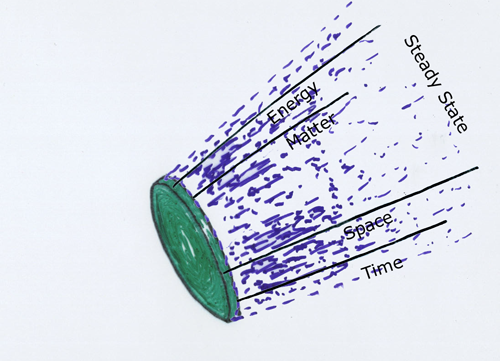

What happens if we extrapolate the dimensions out into the future? The laws of physics indicate that eventually everything will reach the same, uniform temperature. All motion will cease. The universe will be in a state of equilibrium. In other words things will reach a stable, steady-state condition.

This, of course, assumes that nature is a closed system. But what if it is not? It is always perilous to predict the future of any system which is open to influence from the outside, on the basis of its current state. If there is something, or Someone, outside of the system there is no way to predict from within the system itself if, or how, what is on the outside will affect the system – unless the outside entity informs those on the inside what it is going to do. In his book, Miracles, A Preliminary Study, C.S. Lewis provides a useful illustration of this concept. He points out that the laws of physics accurately predict the trajectory of a set of billiard balls. But the actual motion of a ball will be very different from what was expected if, while it is in motion, someone interferes by poking it with a cue. The laws of physics predict what will happen if there is no interference. They cannot predict whether there will be any outside interference and, if so, what that interference will be.

Now if God exists and He has created nature He is, necessarily, outside of nature. In the absence of divine revelation there is no way to predict, from within nature, whether and how God will interfere with nature. Fortunately, we are not totally in the dark. Assuming that the Bible is what it claims to be – a divine revelation – we do know how God will interfere with the natural course of events. Nature will never reach steady state. A day is coming when God will call a halt to everything. Nature as we know it will cease to exist. The predictions of physics about the end-state of nature are wildly misleading, even though the laws are perfectly consistent and accurately describe current physical reality.

What do the physical laws tell us about origins? Following the laws backwards in time, they indicate that all of nature originated from a singular time and place. Scientists call this point in space-time by different names. Some refer to it as the singularity. Others call it the big bang. (For purposes of this discussion, whether the dimension lines come to a sharp point as shown in the diagram, or whether they form a smooth curve as claimed by Richard Dawkins, really doesn’t matter.)

But we again have the problem that physics cannot tell whether and how something, or Someone, outside of nature may have interfered in the past. It takes divine revelation to disclose it. Assuming that such interference has occurred, then just as the laws of physics point to a very misleading conclusion about the end of nature, they also do not give an accurate picture of its beginning. Divine revelation tells us that nature never was at singularity as predicted by the laws. Instead, nature as we know it came into being by a creative act. There is no contradiction. There is no inconsistency. In order for nature to function as it does, the laws must be as they are. It couldn’t be otherwise. But it simply does not follow that nature had its origin in a singularity. We can learn very little about the actual age of the universe or our earth by looking at present conditions.

A gaming metaphor

Let me give you another illustration which might make things a little clearer.

Look at this ‘screenshot’ from a hypothetical role-playing game. A character, let’s call him Gus, lives in, and travels through, a virtual world. From his perspective the mountain in the background is many miles away. The comparatively small hills in the foreground have eroded to their current state through countless thousands, or millions of years. The road he’s walking on was built by means of a government public works program and took a decade to complete. The ruins he’s passing are the remains of a previous civilization which was destroyed 500 years ago.

Gus has freedom of action. He can make decisions and react to his environment. He interacts with other characters, and they with him.

There are several important points to note about this game: a) The game program and the rules which define the game are consistent and well-ordered. If they were not, either the computer would ‘hang’ in some undefined state or behave in some unpredictable (and therefore, unplayable) way. b) Though Gus and the other characters are autonomous in the sense that they can ‘reason’ and make their own decisions, their conduct is constrained by the limits of the program which defines their environment and what actions are ‘legal.’ In other words they cannot, by definition, do anything which violates the programming of the game. c) The state of the virtual environment in which Gus and the other characters find themselves indicates little, or nothing, about the history of the game itself. d) The rules which govern the environment and how the characters behave, do not predict accurately either how the game began or how it will end. e) The game is not a closed system. It is subject to interference by any number of outside influences. f) By observing their environment the characters in the game might be able to infer the existence of a programmer and a few of his characteristics but, in the absence of communication from the programmer, it is impossible for the characters to ever know him.

Now think about the parallels between this virtual environment and our own experience. a) Nature is governed and controlled by consistent and predictable laws. If it were not, we wouldn’t be here to contemplate it. b) We possess free will and, within broad limits, are autonomous. Yet we, too, are constrained by the limits of our environment. Nature is very unforgiving when we try to violate those limits. c) From Gus’ perspective those hills have been there for thousands or millions of years. In reality, however, the programmer built them into the program only last month. Similarly, to Gus the hills look many miles away. From the programmer’s perspective they are only a few pixels distant. Gus cannot even imagine the dimensions in which the programmer lives. If God exists, He is beyond our ability to imagine, let alone comprehend. Our environment may be to us as the virtual hills are to Gus. d) The rules of the game might indicate thousands of years of virtual ‘history,’ going clear back to the formation of the environment itself. It may also project various endings of the environment. In reality, however, someone booted the computer up half an hour ago. Similarly, the actual end might be very different than the projected endings to the game. For example, there is no way for any character in the game to know that five minutes from now someone will hit the computer’s off switch. Similarly, we cannot say anything definite about either the beginning or the end state of nature merely by observing the current state of affairs. In the absence of revelation, there is no way for us to know anything about its true origins or ending. e) The course of the game might be altered drastically by external input from keyboard or mouse. The characters within the game have no way of knowing when or if such interference will occur. Similarly, if nature is not a closed system, we have no assurance that there will not be interference from the outside. f) We’re like the characters in the game. We may be able to infer the existence of a Creator from what we observe about our environment (Romans 1:20 says that His power and divinity are clearly recognizable) but, unless God chooses to reveal Himself, there is no way for us to really know Him.

Do you think my metaphor is far-fetched? Have you ever heard of the a-life movement? (Sometimes also spelled, alife.) It stands for ‘artificial life.’ There really are a bunch of people out there who are trying to write computer programs which not only simulate life, but produce life. A while back I was browsing the shelves at the local library looking for a book on Java programming. In the process I ran across Creation: Life And How To Make It by Steve Grand. It was a fascinating, yet somewhat disturbing read. Though I disagree with the man that we humans will ever be able to truly create life, he was able to program critters which did show some of the characteristics of living things. (The program is called Creatures.) One of the interesting issues which was highlighted by the program was the right of the creator to also kill or destroy the critters he created. That’s a very important insight which I only obliquely implied in my game metaphor.

Solomon wrote that there’s nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9). I was feeling pretty smug about my metaphor and how it makes my concept of creation easy to explain. I was congratulating myself for coming up with such a brilliant idea. Well, not too long ago, I was reading an anthology of Science Fiction short stories. One of them was about a programmer who created a virtual environment. The characters in the environment are alive and gradually develop the technology to make computers. They end up programming a virtual environment with, you guessed it, characters who are alive and able to develop their own technology. The author states in the introduction, that the story bothered him for a long time. He didn’t say so, but I gather it was because it suggests that we, ourselves, may be the product of Someone else’s design. Unfortunately, I didn’t make note of the title of the story, or the author. It may have been Poul Anderson. In any case, there went my claim to an original idea.

All ends well that ends (a summary of this long-winded ramble)

I began this essay by saying that I think much of what is said in the Creation/Evolution debate is irrelevant. The reason I think so is that I do not believe that origins can be correctly derived from observing the present state of things. If God exists, and He created nature, then the beginning must have been very different than projecting physical laws backward in time would indicate. We’re not in a closed system. Therefore, without divine revelation neither the past nor the future is predictable with any certainty. If that is so, then much of the debate is over non-issues. In the long run, arguing about science won’t prove anything. But, then, Paul said it long before I did in 1st Timothy 6:20.

Well, there you have it, folks. Now, if you must, go ahead and break out those hammers and nails.

On Rhetoric

Why do we have sermons, and is there a better alternative?

Those of us who have grown up in the church are so conditioned by the way things are done that we rarely, if ever, ask ourselves why we do it that way. Even those outside the church, but have grown up in a Western culture, have a mental image of what a church assembly is supposed to be like. There’s no doubt that the centerpiece in most protestant church assemblies, whether evangelical, charismatic, fundamentalist, conservative or liberal, is the sermon. But why? What’s so special about sermons and why is so much importance given to them?

Lest I incur the premature wrath of any preachers who happen to read this, let me hasten to say that there is a time and place for sermons. I give them, too. But I do question the emphasis given to sermons and the exalted role they have in the typical church assembly.

Preaching or teaching?

Before going forward with a controversial subject, let me propose a controversial definition. Typically, the delivery of a sermon is called preaching. It may be, but not necessarily, so. If you look at how the words translated ‘preach’ and ‘teach’ are used in the New Testament, it seems to me that they are used in reference to the intended audience, not the style of address. Though there may be some overlap, in most cases, preaching is directed to those outside of Christ, while teaching is directed to those who already belong to Him. A sermon might be the vehicle which is used in both cases. It is the intended audience, not the use of a sermon which determines whether we are preaching or teaching. I don’t expect you preachers to agree with me. Though we’ve never really discussed it, it’s probable that even my fellow Elders don’t.

So, why bring it up? For this reason: I believe on the basis of what I see in Scripture that, in Christ’s scheme of things, the assemblies of the church are intended primarily for believers, and not the unsaved. If that is true, and you insist on preaching to the congregation, you’re talking to the wrong audience. On the other hand, if your intent is to teach – because you are addressing Christians – you need to ask yourself whether the sermon is the best means to do so.

From participant to spectator

But there is another reason to question the sermon style of teaching which is so typical in the churches. Something which impresses me when I read about the churches in the New Testament is the interactive and participatory nature of their assemblies. In a typical assembly, the speaking was not done by just one or two, but by several. Instead of one major speech, there apparently were many short talks. Yes, I’m aware that Apollos was known as an eloquent speaker and that Paul spoke all night at Troas. But they seem to have been the exception and not the rule. And, I wonder if even those assemblies were not far more interactive than the ones we now know.

If I’m right then how and why did the change from the members of the congregation being active participants to largely passive spectators occur? There were many factors which influenced the shift. One was the rise of the hierarchical systems of church government. Along with this was the increasing split between ‘clergy’ and ‘laity.’ It gradually became a fixed idea that only the ‘clergy’ have the right to speak to the assembly. The Reformation recaptured the doctrine of the ‘priesthood of all believers,’ but we have never fully recaptured it in practice.

Another factor which influenced the change in the nature of the church assemblies was the rise of the theological schools. Preference has been given to the formally trained until, in many congregations, it is almost an article of faith that only persons with advanced degrees in theology are qualified to speak. Hand in hand with this was the shift from the Hebrew world-view of a covenant with a warm, caring God who dwells among and fellowships with His people through His Spirit, to the Greek world-view with its emphasis on power and an impersonal and almost mechanistic God. The first emphasized relationship, experience and practical application. The second, knowledge. Anyone can tell others what God has done for him, while only a comparative few feel qualified to speak of God and doctrine in the abstract.

But perhaps one of the biggest factors in the change which took place in the nature of the assembly was the move into church buildings. While there were some benefits, there were also two disastrous consequences from the move into large buildings. The first was that the larger the number of people gathered at one time, the fewer there are, percentage-wise, who are able to actively participate. There simply isn’t time for everyone to share their insights. Secondly, particularly in the era before artificial amplification became possible (most of human history), only a comparative few were capable of projecting their voices so everyone could hear. Naturally, precedence was given to those who were capable of doing so.

The foolishness of preaching

These and other factors may explain the shift from the many to the few, but why have we settled on the form of communication called the sermon? Why has the form of the sermon remained virtually unchanged for hundreds of years? Why are all preachers and speakers, regardless of denominational background, trained in almost identical techniques? Is it because this form of address is particularly effective? On the contrary, I’ve heard and read that experts say that the sermon as a form of communication is particularly ineffective. If that is true, then why do we put so much emphasis on it?

At this point somebody is sure to quote 1st Corinthians 1:21 to me where Paul states that, “… it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe.” (KJV) I’ve heard it explained that though the technique may be foolish (according to communication experts) it is the method God has chosen to save people. No doubt many, have been saved by means of this technique. But contrary to the explanation given, I don’t think that this passage is saying that the particular technique of delivering sermons is divinely appointed as the means to save the world. Remember that definition I gave earlier? Preaching doesn’t refer so much to method of delivery as it does to intended audience. Also, bear in mind that translations other than the KJV (for example see the ASV, ESV, NASB, NKJ and NIV) refer to the message, rather than the preaching, as being foolish. That Paul is speaking of the message which is being preached rather than the method of delivery, fits the context of the next several verses. According to verse 23 the gospel is foolishness to Gentiles. Verse 25 contrasts God’s so-called ‘foolishness’ to man’s so-called ‘wisdom.’

Whence the sermon?

So, if the practice of delivering sermons is not necessarily divinely inspired, and it isn’t particularly effective at communicating, why do we use the technique so much? Well, for one thing, it can be a lot easier than the alternatives. At this point all of you who sweat blood over your sermon preparation each week, probably either want to lynch me or are laughing your heads off. But I’m perfectly serious. I’ve learned the truth of my statement through personal experience. I’ll elaborate in just a bit.

You want to know the main reason we depend so much on trained orators delivering sermons? It’s because we’re stuck in a rut that was carved out for us 16 to 17 centuries ago. There were 3 guys who lived during the same time-frame in different parts of the Roman Empire. In truth, the trend was there in strength long before these guys showed up on the scene, but I think it’s fair to say that they are primarily responsible for digging us into the hole we’re in. They are John of Antioch (349-407), Ambrose of Milan (340-397) and Augustine of Hippo (354-430). Do you know what the common denominator is between all 3? All of them were highly trained in Greek rhetoric (defined as the art of speaking and the principles of composition) before they began their ecclesiastical careers. And, they didn’t leave their training behind when they entered the church. John of Antioch is also known as John Chrysostom which means John ‘Golden-mouth.’ He supposedly was the most gifted orator in the entire Roman Empire. Ambrose taught rhetoric and had a hand in training Augustine. Augustine was arguably the most influential theologian in the period between the Apostles and Luther. His book on homiletics is still in use, and excerpts from his discussions on preaching are still quoted in textbooks on the subject. It is these 3 which set the standard. It is they who taught succeeding generations how to do it. We’ve never recovered from their influence.

Where did they get their theories and techniques of communication? Was it from the Bible? No, it was directly from the Greeks. They merely refined and perfected ideas which had been around at least since Aristotle’s time. Don’t believe me that preachers are still trained in the techniques and methods of the 3 men I mentioned and that they got ‘em from the Greeks? Browse through an older textbook on preaching sometime and you’ll see whether I’m right. I could name authors but will spare you. It can be rather startling to realize that the speaking style of introduction, proposition, divisions, development and conclusion that we’re all so familiar with was actually something which was developed for use in the Greek law courts. Is it any wonder that our minds often associate the word ‘sermon’ with ‘harangue?’

It’s fascinating to me that one of the criticisms leveled at the Apostle Paul was that he was a poor speaker. (2 Corinthians 10:10) While giving a defense of his ministry he admits that he wasn’t a trained speaker. (2 Corinthians 11:6) I understand him to mean that he was not trained in the Greek style of rhetoric which, in turn, was a reflection of the Greek way of thinking. Throughout his letters Paul challenged the Greek outlook and emphasized the inner work of the Spirit. This is the larger context of his statements about God’s foolishness vs. man’s wisdom, love vs. knowledge, strength through weakness, being exalted through humility and so on.

The purpose of the assembly

Aside from the concern that the sermon is really an outgrowth of a Greek world-view in contrast to the Hebrew world-view of Christ and the Apostles, I am of the opinion that by being so locked into the sermon we have lost something very vital. Let me try to illustrate what I mean. Just about any book on sermon preparation will tell you that the intent or purpose of the sermon (echoing Augustine, by the way) is to persuade. The majority of speakers seem to agree because, at least in the congregations with which I am familiar, it is almost inevitable that an ‘invitation’ will be given at the conclusion of the sermon. But what is the assembly for? Yes, Paul writes in 2nd Timothy 3:16 that Scripture “…is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness…” (NIV) and, therefore, if we are going to speak from the Scripture, we are, at times, going to try to persuade. Persuasion is inherent in correction and rebuke. But there should be far more to our assemblies than the attempt to persuade. Another purpose of the assembly is to foster unity. It is also for mutual encouragement and comfort. (Take another read through 1st Corinthians, chapters 12 through 14.) When we make something whose main purpose is to persuade, the centerpiece of the assembly haven’t we gotten something out of balance?

Alternatives

So, with what should we replace the sermon? Mutual interaction as was the norm in the New Testament church. This could take a number of forms. Here are a few suggestions: a) The sermon could be replaced with a number of short talks, or devotionals, each given by a different person. b) A topic or a passage of Scripture could be announced ahead of time and, then, anyone who wants to would be free to share his or her insights on it. c) The time normally given to the sermon could be spent offering encouragement to those in the congregation who are going through struggles, and praying for one another. d) A principle of Scripture could be explained, then the whole congregation could discuss how to actually apply it in every-day life.

Things which hinder

I said earlier that one reason we’re so locked into the sermon is that it’s easier than the alternatives. For example, planning and coordinating an assembly with just one speaker can be hard enough. But it can be far more complex if you have multiple speakers. It takes much more communication to make sure that everyone knows what they should do, and when to do it.

Another barrier to overcome is the fear of failure. What if you can’t pull it off? What if the assembly doesn’t work as envisioned? What if the various pieces don’t fit into a harmonious whole? What if you open things up for input from the congregation and nobody says anything? One virtue of an assembly based on a sermon is that it’s predictable.

Then, there’s the matter of expectations. The truth is that most people in our culture expect our assemblies to be based on sermons. A different format can be very disconcerting or upsetting to them.

There’s also the fear of interruption. When we get up to speak, we have a certain amount of material we want to get through. If we allow input from the congregation, it has the potential to take things in a different direction than anticipated. We might not be able to cover all the material we had planned on presenting. Even worse, an interruption; a question from the congregation might break our train of thought.

But the biggest problem of all is our fear of the loss of control. Let’s face it. We like to be in charge. When we’re delivering a sermon, we know exactly what we’re going to say and how we’re going to say it. The whole assembly is built around our message. We control what happens. But when things are opened up so everyone can participate, all that changes. The certainty is gone. What happens if somebody says something which is contrary to sound doctrine? Even worse (from our point of view) what if they say something embarrassing?

Some benefits of replacing the sermon

What’s the benefit to opening up our assemblies to interaction and participation? There are many. a) We expect people to grow spiritually, yet we give them very little opportunity to express themselves which is often one of the quickest ways for them to grow. Teachers always learn more than their students. It’s an incentive for people to learn if they must organize their thoughts and present them. b) Each person’s experience with Christ is different than anyone else’s. By sharing with one another, all benefit from the different perspectives and insights which are expressed. The congregation as a whole becomes more well-rounded than if it hears from only one or two. c) Problems and burdens come to light which would otherwise remain hidden. It also allows those with burdens to experience the the comfort and the support of the entire body. d) It gives people the feeling that they are part of the body. It gives them a stake in the success of the congregation. e) It gets people used to speaking about Christ to others. As they gain confidence from doing it in the safe environment of the assembly, they will feel more inclined to do it outside the assembly. f) We don’t get good at anything unless we have the opportunity to practice it. If we want to develop good speakers, we must give people the chance to do it.

Practical steps toward participation

It may not be possible to totally restructure our assemblies all at once. If, for no other reason, expectations will prevent it. People need time and teaching before they get used to the idea of participating. It won’t happen overnight. Some will never be comfortable with all I’m suggesting. Even in the congregation where I serve, we have not been able to achieve the level of participation I would like to see. It’s a difficult problem. But there are some things which can help move things in the right direction.

There’s one area where it should be fairly easy to increase participation. In the tradition from which I come, the Lord’s Supper (Communion, or the Eucharist) is celebrated each Sunday. It is preceded by a short meditation. Ask different men in the congregation to prepare and present these meditations.

Another relatively minor change which would increase participation is: Instead of the song leader and the speaker of the day always being the ones who pray during the assembly, have various members of the congregation give the prayers. In the same vein, you might be able to introduce other small chunks of content, such as Scripture readings, which could be done by various members.

If you wish to retain the sermon format, at least consider expanding the number of speakers. For example, one of the qualifications of Elders is that they be able to teach. But, in many congregations I have known, they do little or no teaching or speaking. In my view, they ought to be rotating through the pulpit.

If, for whatever reason, you can’t change the format of your assemblies, then consider allowing a time of sharing and interaction afterwards. For example, you could have a period when people could discuss the sermon they just heard with the emphasis on how it applies to their own lives.

If you can’t restructure your assembly, then restructure your class times. Assign short lessons and topics to various people. Announce a topic or portion of Scripture and open the session up to anyone who wants to share their insights on it.

These are just a few suggestions. If you really catch the vision of the value of participation and interaction, I’m sure that you will be able to think of many ways it can be encouraged which fit your particular situation.

It may not always be welcome. In fact, some will be downright hostile to the idea of opening up your assemblies to participation and, heaven forbid, not having a sermon. Even (or especially!) your fellow leaders will be uncomfortable with the idea. It’s likely that you will lose some people. However, I am of the opinion that the more participation and mutual ministry we have in our assemblies, the closer we will be to the New Testament ideal and the stronger we will be.

What size?

Back in the 1980’s one of the most popular books on management making the rounds was In Search of Excellence by Peters and Waterman. Not long after the book was published, several of the ‘excellent’ companies they wrote about ran into trouble. Some of the principles and ideas discussed in the book have since fallen from favor, too, but one of them has intrigued me from the time I first read it.

Scaling down for growth

The authors wrote that many of the excellent companies ignored theoretical economies of scale and deliberately designed their systems and plants to be sub-optimal. It turns out that by keeping things small, these companies were able to achieve efficiencies which more than made up for any economy of scale. They reported that things started to go wrong whenever there were more than about 1,000 people under one roof.

As I recall, it was around this same time-frame when the church-growth movement really took off. Seemed like everybody started talking about how to boost attendance, membership campaigns and the need to build bigger facilities. The drive toward the mega-church was on.

Along with everybody else, I attended workshops and seminars that were supposed to tell us how to make it all happen. I was probably as caught up in the excitement as anybody. Yet, that figure of 1,000 people continued to haunt me. Was it possible for a congregation to get too large? Was there a point where friction and inertia overcame the advantages of a large body count in the pew? I recall making the suggestion that when a congregation got to about 500-600 maybe it would be best for it to hive off a separate group of 200 or so instead of trying to grow larger.

A glass ceiling

In truth, though, the question was largely academic. In spite of best intentions and efforts, most of the congregations I knew remained small. It seemed impossible to grow much past the 100 mark. In the arrogance of youth I laid much of the blame on inept leadership. To my critical eyes, the reason for the failure to grow beyond a certain point was that most church leaders were woefully ignorant of the basics of management. As if I, who had never had to manage anyone, knew anything about it!

Time moved on. So did I. I left a small congregation which had plateaued for a much larger, growing one in a different city. Through various circumstances, the Lord knocked some of arrogance out of me. I also found out that large congregations can start having serious trouble long before the 1,000 member mark is reached, or even the 500-600 I had proposed. If there was an ideal size, I had not yet observed it.

Re-thinking

Fast forward 20 years. The Lord called me and my family to be part of the leadership team in a new church plant. Suddenly, the issue of church size became an issue again. Were we going to embrace the mega-church concept, or would we choose a different model? For many reasons we deliberately chose to keep the size of the congregation relatively small. How small? We didn’t know, but decided to grow by multiplying congregations rather than trying to increase congregation size beyond a certain point – whatever that point is.

Is there an ideal congregation size? At what point should a congregation spawn a new one? A while back, my brother-in-law sent me an email in which he passed on the tidbit that Reuel Lemmons (a well-known leader among the Churches of Christ) had said that beyond a size of 150 we can’t know everyone very well. The implication was that congregations should be somewhat smaller than that. Since my b.-in-l. was unable to provide references and Lemmons is dead, that was little more than an interesting factoid. Then, I read the book, Radical Restoration by F. LaGard Smith. (An excellent and provocative read, by the way.) In it he, too, mentions the figure of 150 and, more importantly, gave a source: The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell, who, in turn, draws on the studies of Robin Dunbar.

Channel overload

The key insight is that we are only able to handle a limited amount of information before our minds are overloaded. In social contexts, on average, we can only handle about 150 channels of communication and/or interaction. In other words, we are capable of relating to only about 150 people well, and knowing them in the sense of how they are interconnected to us and with one another. Beyond that number, interaction and communication breaks down.

Something which concerns me is the sheer number of references pointing to Dunbar’s work. Now that I know the source, it seems like references to the “Rule of 150” are popping up everywhere. It feels like everyone is jumping on this single-source bandwagon. It has the feel of a fad about it. Frankly, I’m skeptical of Dunbar’s theories. Anything which is based on evolutionary psychology and the relative sizes of primate brains raises a red flag or two. But even if Dunbar’s theories prove to be pure hokum, that doesn’t invalidate the observations about the limitations of social channels. We all know that relationships start to break down within a group at a certain level. That fact remains even if the speculation about how the fact came about is moonshine. The real question is where that breakdown begins. Is 150 the right number? It feels right. I would feel a lot more comfortable if there were more independent confirmation but, I’m willing to accept the number of 150 pending further inquiry.

Adding complexity

“Hold it!,” you say. “If this number of 150 is so all-fired important, then how come so many groups exist which are larger than 150? What keeps them together?” It’s not that groups larger than 150 can’t exist. Obviously, they do. But Gladwell points out that the number of 150 is really a point of complexity. Below it, we can keep track of one another informally. Above it, we must introduce systems and procedures in order to function smoothly. If he is correct, this is a major reason why so many congregations find it impossible to grow much beyond 100 or so. They simply have not developed, and put in place, the organization which will allow them to. There are a lot of other factors which have a bearing on growth, but that’s a subject for another blog.

A practical consideration

If the observation about the limits on social relationships is correct, it sheds light on something which has often been commented on in many congregations. Christians should be reaching out to their friends and acquaintances with the gospel message. Yet it seems that most Christians become ineffective in reaching others within a few years after their own conversion. Is it possible that as a new convert becomes more and more integrated into the church that we overwhelm his social capacity? He has no room left for relationships outside the church body. Since he has no relationships his influence is minimized. If this is true, it is a powerful argument for keeping the size of congregations relatively small.

Acting as a body

There’s another practical implication of this social channel limit business. Gladwell points out that a group has what the psychologists call “transactive memory.” That is, we remember more as a group than we do individually. We rely on others to fill in the details we have forgotten. The same is true of skills and talents. When everyone knows everyone else, tasks are naturally delegated to those who are best suited to perform them. When you need an answer, or you need something done, you know who to go to. But what happens if the group is too large? The social and relational connections are broken. You no longer know everyone, and because you don’t, you no longer know who to go to for help.

After pondering this a bit, I couldn’t help but think of what Paul wrote in 1st Corinthians 12. There Paul compares the church to a body made up of many different, yet interdependent, parts. The eye is not the same as the hand, and both need the other in order to function properly. But what happens if the eye doesn’t know about the hand? How can they possibly work together as a body? The implication is startling: If a congregation is going to function as a body, we must keep its size within our social channel capacity. The natural upper limit, seems to be about 150 people.

The Jerusalem church

Come now! If all this is so, what about the early church? 3,000 people were added to the church in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost alone. Okay, let’s look at it. We tend to think of the church in Jerusalem as one big, monolithic, entity. It’s true that at least for a while the church met in the temple courts. But there is something else which didn’t really make an impression on me until I started thinking about this thing of limits. Not only did they meet in the temple courts, they also broke bread in their homes. (Acts 2:46) This implies that the larger group was actually composed of many small ones. How many and how small? Who knows? But if the groups averaged 50 people, just 60 groups would have accommodated the entire 3,000 converts. 50 people in one home? Those who have grown up in the West have a hard time imagining it, but I’ve often seen that many gathered in one small home in the East. Hey, we once crammed 21 people into a Jeep station-wagon! Well, what about leaders for these groups? The 120 believers which met before Pentecost had been taught directly by Christ. It’s more than likely that a number of them were among those Christ sent out on preaching tours. Under the oversight of the Apostles, these believers could easily have provided the leadership the various groups needed. Another source of leaders was the converts, themselves. There must have many men of high caliber among them – men such as Philip and Stephen. Acts 6:7 says that a large number of priests were converted, also. Here were competent men, already highly trained in the Scriptures, who could have stepped into leadership roles almost immediately. As I think about it, it seems very likely that the church in Jerusalem was able to easily keep below the 150 people limit by constantly adding small groups.

Lower limits and the military metaphor

If there is a natural upper limit to congregation size, is there also a lower limit? We don’t like to think so. After all, Jesus said He would be with even 2 or 3 who gather in His name. (Matthew 18:20) Yet, unless those 2 or 3 are extra-ordinarily gifted, it is hard to imagine them as a fully functioning body. Another scriptural metaphor for the church may shed some light on the question of a effective lower size limit for a congregation. Christians are called soldiers. So, what can we learn from the size of military units? Ancient armies were often organized by multiples of ten. For example, in both the Roman and Mongol armies, the smallest unit was composed of 10 men. Ten of these units formed the next grouping, and so on. In the modern US army, the smallest unit capable of independent movement is the platoon. Light infantry platoons are composed of 3 squads of 10 men. Based on this, which is the distilled wisdom from thousands of years of practical experience, it is tempting to say that a congregation less than 30 is not viable. At the least, it is probably too small to be stable, or effective. This may be why so many house churches don’t seem to live up to their promise.

Interestingly, a company in the US army, which is the basic military unit which can perform a battlefield function on its own, is composed of 100 to 200 men. This fits amazingly well with the notion of the “Rule of 150.” A company is generally small enough for everybody to know each other and everybody’s capabilities. Even those companies which are larger than 150 can function well because of the structure and organization imposed on military units. They have compensated for the limitations of our ability to form natural, informal relationships with large numbers of people, by adding structure.

Summary

Does structure, or context, affect the size of congregations? Yes, but that’s for a different entry. For now, I’ll just go on record to say that a congregation should probably be larger than 30 people, but not more than 150. When it grows to about 120 or so, it should begin to plan seriously to multiply by dividing itself.

Thank God For Gutenberg!

Wherein PresbyterJon lists some of the books he’s been reading…

One of my vices is reading. No, I didn’t say that I read vice! Reading, itself, can easily turn into a vice for me. You see, I read not only to get information and to continue learning but, for me, reading is a great pleasure. It’s my preferred method of relaxing and getting my mind off of problems and difficulties. Of course reading can be a great help in finding solutions to problems, and a lot of my reading is for that purpose. But it’s the pleasure part that gets me in trouble. I find myself letting books get in the way of doing work I ought to be doing. There are times when I have to consciously avoid visiting the library lest I be tempted to neglect necessary tasks. Fortunately, I’ve been blessed with the ability to read quickly.

The blessing of books

Over the years I’ve had many opportunities to think about the incredible blessing of books. Have you ever wondered what our world would be like without the invention of movable type? It was movable type which made the printing of inexpensive books possible. Without inexpensive books, only the wealthy would have access to much of the information in the world. We would be far less informed and far less able to verify what we’re told.

Movable type and literacy

Not only did the invention of movable type make the printing of books inexpensive, and therefore the availability of books widespread, it also had a profound effect on literacy. This goes deeper than simply making books widely available. Have you ever stopped to think about systems of writing and the impact of technology upon them? The English language is blessed with a relatively simple alphabet of only 26 characters. If you include both upper and lower case letters, numbers and punctuation, the entire English writing system can easily be represented by just 94 or so distinct characters. This is not so in other traditions. The writing system in the area of Asia in which I grew up consists of some 39 letters – depending on how you count them. English spelling may be crazy, but how would you like to have to contend with 4 different Zs? While it does not have the concept of upper and lower case, the shape of most letters changes depending on the location in a word. Some letters must connect to the letter on either side. Some may not, or only connect on one side. To complicate matters the vertical placement of the start of a word depends on the first letter and how long the word is. In some cases, some letters have descenders while in other cases they don’t. And don’t get me started on diacritical marks! (Some vowels are distinct letters, while others are only indicated by diacritics.)

I’ve never been able to compute the number of possible permutations of letter shapes, but it is probably in the 100’s of thousands if not millions. Yes, there are mono-spaced fonts based on compromised initial, middle and final shapes for each letter but, as a general rule, they look rather hideous. Is it any wonder that, until recently, the majority of books and newspapers in this language were hand-written by calligraphers? Is it any wonder that decent word-processors for this writing system weren’t developed for a couple of decades after they became common-place in English speaking countries? The word-processors are based on ligatures rather than discrete letters. The best of them boast some 15 to 20 thousand ligatures and, I can tell you from my own experience, that it is still far too few. I often run into letter combinations which just don’t look right.

Now think about the practical implications. I’m convinced that one of the major factors for why literacy is still so low in the area I grew up is the complexity of the writing system. It’s not a trivial task to learn it. It’s one reason why comparatively so few books and other material are written. It’s also one reason why the English language is becoming so universal – the writing system is simply much easier to deal with.

Though the English alphabet never was as complicated as the one I’ve mentioned, the invention of movable type is partially responsible for its simplicity. Our writing system was simplified to compensate for the limitations of the technology. To a certain extent, beauty was sacrificed to utility and, because people were willing to make that trade-off, mankind has been immensely blessed by the rapid spread of knowledge. It has also given innumerable people an outlet for self-expression. If someone has something to say, he has a far greater chance to put it in a form other people can access.

Library access

The catch is whether people really can access it. The production of inexpensive books is only part of the equation. Unless the books are distributed, they do little good. Even if a book is inexpensive, it still won’t be widely read if people can’t afford to buy it. For most of history, books, no matter how inexpensive, have been a luxury. It really wasn’t until the 20th century that most people in the West could afford to buy many books. But there was something else which made a huge difference, at least here in the US. No matter what you think of the the so-called “Robber barons” of the last half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, we owe a lot to them. Yes, they were manipulative. Yes, they exploited. Yes, they can be accused of unfair labor practices – and all the rest of it. Yet, it has to be said that they amassed their personal empires and fortunes not so much by destroying, as so many have done throughout history, but by building up the infrastructure of this country. As despicable as some of their actions may have been, they laid the industrial and financial foundations of our present society. They also did something else. After they had amassed their fortunes, most of them turned to philanthropy. Part of that involved endowing libraries. All across this nation there are public libraries which came into existence because wealthy people decided it was important that ordinary folk, people who could not afford to buy them, have access to books. Those libraries have helped educate whole generations. Those libraries have enabled generations to dream and to pursue opportunities which, otherwise, they might not have known even existed.

Libraries and trust

Libraries by themselves, however, do not ensure the wide distribution of knowledge. There is another factor. Without that factor the libraries would soon be forced to close or drastically alter their methods of operation. In fact, libraries as we know them, could not exist in the country in which I grew up. What’s the factor? It’s called, trust. It’s a basic respect for the property of others. It’s recognizing that others have just as much right to access as I do. Think about it. When I walk into a library, no one checks to make sure I have a card giving me the right to be there. I can take as many books off the shelf as I want. (The last time I checked, the number of books one person could check out was so ridiculously high that, in effect, there is no upper limit.) They let me take the books home. No one inspects my bag as I walk out the door of the library to make sure that I’ve checked the books out. They trust me to let them know which books I’ve taken. They even allow me to check the books out of the library myself. They trust me to bring the books back. They don’t even hound me about paying the fines I’ve incurred by keeping books past the due date. Though there are many fine people in the country where I grew up, that kind of trust simply doesn’t exist in society as a whole. The books would disappear off the shelves, never to return, in short order. Because trust and integrity does exist in this society, library books have a wide circulation. Because most are willing to put the general good ahead of their own selfish desires, all benefit, not just a privileged few.

An even bigger revolution

Now, as big as the revolution brought about by the invention of movable type was, we’re in the middle of one which may prove even bigger. Let’s face it. Even though printing is cheaper than ever before, and the production of books is relatively inexpensive, it still takes quite a bit of money to print one – not to mention the expense of making any revisions! Also, regardless of whether they’ve brought it on themselves or not, a relatively small percentage of the world’s population has access to libraries. The Internet is in the process of changing all this. Not only is the Internet replacing physical objects (books you can hold in your hand) with something intangible (letters formed of light), it’s made it possible for more people than ever to have a voice and to have access to the voices of others. Hey, without the Internet, it’s highly unlikely you would ever hear of PresbyterJon, let alone read what he has to say! The Internet has brought us one step further out of the material world, and one step closer to mind communicating directly to mind – at least for those who use Western alphabets. (The Internet, and particularly the Web, was designed for English and other European fonts. Unfortunately, designing and maintaining a website in the writing system I mentioned earlier is a nightmare. To make it look halfway decent you have to first render text as a graphic rather than as discrete letters which can be assembled and rendered directly by the end-user’s browser. That means that once text has been written it can no longer be manipulated, corrected or changed unless you have access to the original. This severely constrains what can be done. I can only hope that the limitations of the technology will drive the same kind of simplification that movable type sparked for English.)

A book list

Wow! After chasing down that long rabbit-trail, let me just say that though I spend long hours in front of a computer screen; though I certainly am not blind to the benefits of the Web and the Internet, I still like the feel and utility of the real thing. I still like to lay down on the couch with a good book.

So what books has PresbyterJon read? There are far too many to list, but the following may be of interest to you:

Biblical Studies

A Shepherd Looks at Psalm 23 by Phillip Keller. An excellent and practical look at what is perhaps the most famous and best loved of the Psalms. Anyone aspiring to the work of Pastor should study this Psalm in order to gain a better understanding of what shepherding is all about. (The term ‘Pastor’ is also translated as Shepherd and, in New Testament usage, is equivalent to Elder or Presbyter.)

Hand Me Another Brick by Charles R. Swindoll. This is the best exposition of the book of Nehemiah I have ever read. It’s a ‘must read’ for anyone in leadership.

Decision Making and the Will of God by Garry Friesen with J. Robin Marson. This book helped me untangle a few things during a certain portion of my life. It’s the best discussion of biblical decision making that I know of.

What the Bible Says About Covenant by Mont W. Smith. This book was the first comprehensive treatment of the concept of covenant that I had ever read. It helped bring both the Old and New Covenants into perspective for me.

Heaven by Randy Alcorn. Christians tend to have a lot of misconceptions about heaven. This is a refreshing, and quite comprehensive, look at the subject. Very thought provoking and faith building. Not only is this a good read, I appreciate the author’s humility and frankness. Though he is candid about his premillenial beliefs, and there are several portions of the book which are colored by that viewpoint, he is not dogmatic about it and leaves open the possibility of being wrong.

As a general rule, I don’t recommend commentaries – at least to beginners. Not only do they promote laziness by encouraging students to short-circuit the process of studying things out for themselves, commentaries can be dangerous. A good many of them are written by scholars who do not believe some of the foundational truths of the Christian faith such as anything which involves miracles or predictive prophecy. Unless used with caution, commentaries can undermine faith. One exception to this is the College Press NIV Commentary. It’s an exegetical commentary, meaning that, while it attempts to give the meaning of each verse or passage, it does not go into many details of structure, grammar or the gamut of scholarly opinion. One of the strengths of this series is that, by and large, the doctrine is sound.

If you want a scholarly commentary, the best contemporary series I know of is the Word Commentary. It still must be used with caution but, in contrast to some series I could name, the scholarship is quite good and consistent from one volume to the next.

Revelation, Four Views edited by Steve Gregg. In spite of its title, Revelation remains a mystery to most. This book gives a good overview of the four major ways the book of Revelation has been interpreted.

Nobody Left Behind by David Vaughn Elliot. An important corrective to the doctrine of Dispensational Premillenialism which is so ingrained into popular evangelical thought. The title is a deliberate take-off on the ‘Left Behind’ novels.

Church

Radical Restoration by F. LaGard Smith. This book raises profound questions about many aspects of church tradition. I had already come to many of the same conclusions on my own, but Smith expresses it far better than I could. Well worth reading and thinking about – even if you don’t agree with the direction the author takes.

The Worldly Church by C. Leonard Allen, Richard T. Hughes and Michael R. Weed. This book exposes a number of the trends which are taking root in many of the churches with which I am acquainted. It not only identifies the vulnerabilities of those of us who trace our heritage to the Restoration Movement, but suggests correctives. This book is actually the middle one in a series of three. The other two are Discovering Our Roots and The Cruciform Church. Of the three, I found this one the most rewarding, though all three are worth reading.

Death of the Church by Mike Regele with Mark Schulz. A fascinating look at the waves of change which are about to engulf the church. The argument of the book is that the church, as we know it, must die and remake itself in order survive the next few decades. I was particularly intrigued by the discussion of inward and outward looking eras and the impact of generational cycles.

The Open Church by James H. Rutz. Though at times flippant, over simplified and written in a deliberately provocative style, this book presents a refreshing alternative to church as we know it. The author points out that much of what we do is not modeled after the church in the New Testament, but is left-over baggage from cultural and ecclesiastical practices which were brought into the church from the outside.

Missions

Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours? by Roland Allen. This one ought to be required reading for all church leaders, not just missionaries or those on missions committees. Along with my own experiences and observations, Allen has radically changed my thoughts and my approach to mission work. The book was first published in 1927 and was written in a formal style, so some may find the language a bit difficult to understand and plow through. Also, Allen was an Anglican and he wrote from the perspective of a hierarchical system that I don’t agree with. In spite of those caveats, it is a highly rewarding read. Though expressly written about mission, the principles are applicable in any church.

The Spontaneous Expansion of the Church and the Causes Which Hinder It by Roland Allen. This is the sequel to Missionary Methods. Though a harder read, it is also more provocative and hard-hitting. Allen raises a number of questions which are well worth thinking about.

I sort of grew up on Kipling. Though it is not primarily about missions, The Naulahka by Rudyard Kipling fills an important need. It does an excellent job of describing the culture shock which occurs when two diametrically opposed value systems come into contact. In spite of the differences, we can find understanding in our common humanity.

Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon. Yes, this is the book upon which the Broadway musical and the movie The King and I, are based. Anna’s character and her actual role in the Kingdom of Siam have been the subject of much debate. But fairly recent discoveries of some long-lost letters written by the king to her, substantiate what Anna wrote about her time as a school teacher and royal secretary in the palace. I believe the accounts she wrote are true. This book is well worth reading. It’s an amazing testimony of the incredible impact one person can have in just a short time.

The Little Woman by Gladys Aylward as told to Christine Hunter. This is another story that tells about the influence one person who is sold out to God can have.

DMZ by Jeannette Windle. No one who has spent much time on the mission field comes back unchanged. The children of missionaries, in particular, often have a hard time adjusting to, accepting or even understanding the sacrifices and decisions their parents made. Written by a former missionary, this book is actually a thriller. Even somewhat of a techno-thriller. Aside from being an interesting (and clean!) read, what I appreciate about the book is that it confronts the questions and struggles that children of missionaries go though. I also appreciate the answer the book gives to those who claim that missionaries destroy and exploit other cultures.

History/Biography Related to Biblical Themes

Herod, Profile of a Tyrant by Samuel Sandmel. This book gave me a greater understanding, not only of a man who played a key role in the biblical story, but of the times just prior to Christ’s birth. It was helpful to understand the political context into which the Savior was born.

Mary Renault has written a trilogy about Alexander the Great and the period immediately following his death. The books are: Fire From Heaven, Persian Boy and Funeral Games. We sometimes forget, or don’t realize, how blessed we are by our heritage. We in the West live in an era and a culture that, no matter how badly it wishes to deny it, was shaped by Christian thought, ethics and morality. This trilogy should shock you. It helped me realize just how dark a world Christ was born into.